“Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early and continuous delivery of valuable software.”

The Agile Manifesto

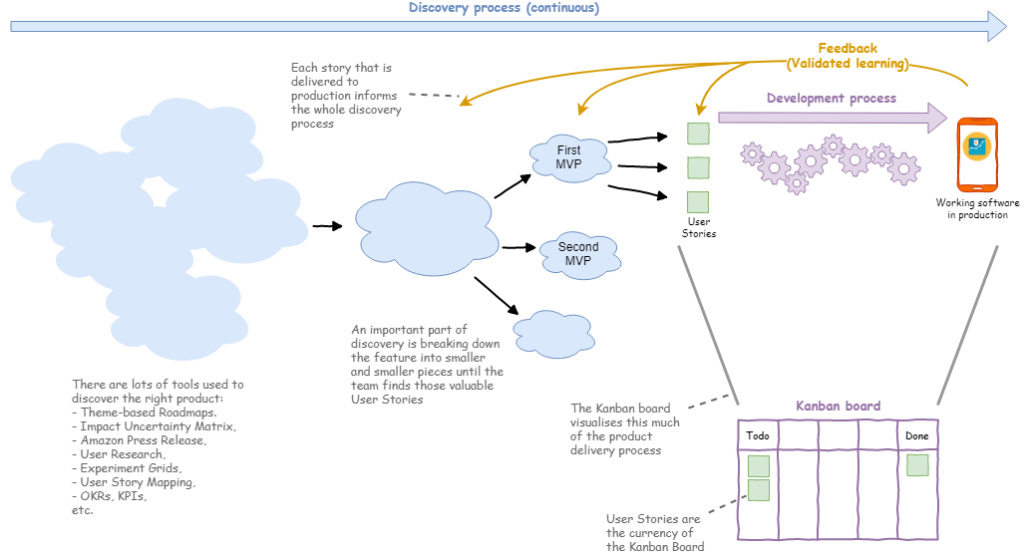

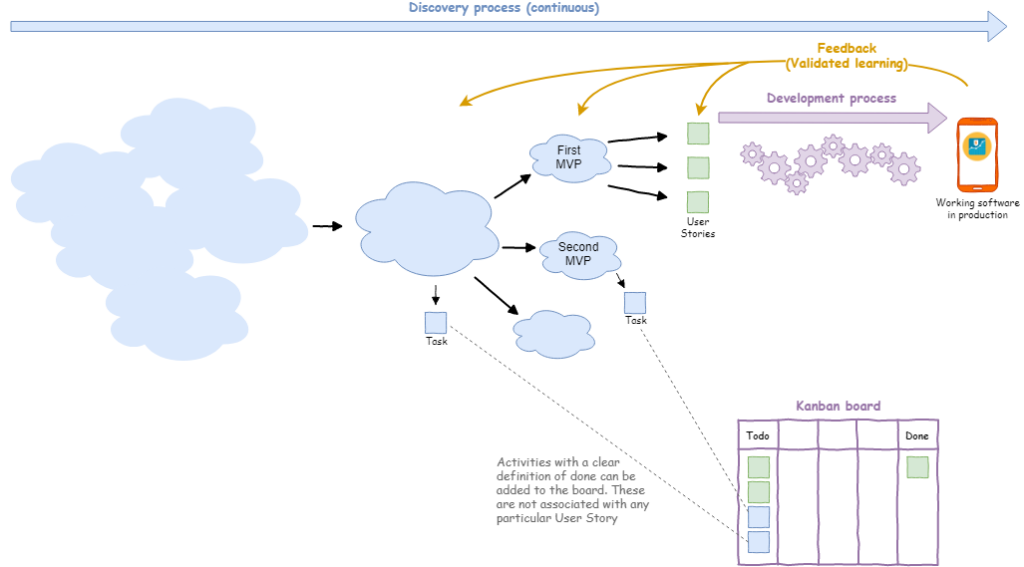

When I am working with cross-functional development teams, I use the storyboarding technique to help the team break down their work. This usually involves identifying an MVP and creating a prioritised backlog. I also encourage the team to use the INVEST criteria to create good quality stories. So far so good.

What happens next is that the team start development with the goal of delivering the MVP to customers. The problem is that the MVP is still a finished product that usually contains many stories (i.e. several weeks of work) and there is little or no customer collaboration once the concept phase is over and development starts.

Delivering an unfinished MVP is often not considered valuable for customers, but it should always considered valuable for the development team, because getting feedback is critical to building the right thing. There are three major obstacles to making this happen.

Lack of alpha/beta users

Even the very earliest releases of an MVP (e.g. “Hello world”) can be delivered, it is just a matter of a matter of defining who the customer is and setting the right expectations. These can be real customers that are willing to test features under development in return for some discount later, or else they can be people in the organisation (but not the team) that are interested in the success of the product; stakeholders are good candidates for example.

The team of course should continue to do demos of the product, both within the team and the organisation, but this should not be used as a substitute for hands-on customer testing.

Packaging unfinished features

Ideally, each story adds some piece of value while maintaining the conceptual integrity of the product. In other words, the customer should still always have a good user experience, and can readily distinguish limited functionality from buggy software. This is extremely important because what the developers are interested in is valuable feedback.

If the developers do not package the story in a good way, leaving broken links etc., then it will end up wasting the time of the customers and the developers. It also affects customer engagement negatively; customers want to know that the developers treat their time as valuable. Customers are also less likely to test exhaustively if they know that some things are broken (they just don’t know which ones).

Overhead of intermediate releases

“Deliver working software frequently” is one of the principles of the Agile Manifesto. Automating the release/deployment process is essential to achieving this. The harder it is to make releases, the less frequently the team will want to make them. And in the case of unfinished features this is only going to be more so, if at all.

Overcoming inertia

The combination of these three obstacles can create a huge inertia in teams to make early releases. So is it worth the hassle of making early releases? The answer must be yes. Making frequent releases is an essential tool of any Agile team regardless of whether they are delivering an MVP or incrementally improving an existing product.

Packaging the unfinished feature is also good developer practice, after all, who knows when time or money will run out? (“Responding to change over following a plan”).

Utilising alpha/beta testers outside the team is also a good way to create visibility for stakeholders who have a natural incentive to see the end result first-hand. Also, delivering what you’ve done so far is always much better than wasting time giving estimates (“Working software is the primary measure of progress”).